©2007 William Ahearn

With apologies to Manuel Puig

Nostalgia, that harmless longing for a familiar time or place,

was considered a serious psychiatric condition in the 18th and 19th centuries

manifested in symptoms that we now call post trauma stress disorder and anorexia

nervosa. At least that is the contention of Ed Brown in his essay, Notes

on Nostalgia. The annals of the so-called science of psychiatry are

filled with affliction definitions such as hysteria and homosexuality that

have since faded as disorders and while I would love to spend this time trashing

the hacks and quacks of the post-phrenology escorte de lux psychiatric-industrial complex,

I’m more concerned with the mutating act of watching films.

This occurred to me the other day when I was down with a case of

the flu and, bundled up in bed, my tissues and chicken soup on the nightstand,

I loaded the DVD of Orson Welles’ “The Lady from Shanghai”

into my laptop. It had been one of my favorite films some thirty years ago,

and I wondered if time and distance would diminish my appreciation of it.

Somewhere between plugging in the headphones and sliding the DVD

into the drive, I realized that I was going to watch a film while cosseted

by bedcovers and the comfort of soup and escorte bucuresti thought back to my days as a kid

in Queens, a borough across the river from where I live now and a place I

remember more than I revisit. This isn’t the time to recount a miserable

and misspent childhood and the ritual and rigmarole of my Saturday afternoon

adventures at the movies, so suffice it to say that I was pretty much left

to my own devices.

In those days there were two movie theatres and one certified

movie palace within walking distance. The palace was one of the Loew’s

theatres with curved balconies and projected onto the dome above the seating

area were flowing clouds amid a sky of stars and it, along with the Astoria

Theatre, was on Steinway Street, a bit of a walk yet not that far if something

really, really good was playing. The other theatre was the Hobart and it was

a block from my house and ran movies all day long and you could see them all

if you had the entry fee of fifty cents and a taste for second-run features,

B movies and low-budget horror flicks. The aisles of the Hobart were patrolled

by elderly matrons dressed in white and armed with flashlights ready to pounce

on teens necking in the balcony or kids tossing handfuls of Jujubes or Red

Hots at nerdy rivals. If you were really rowdy the matrons would get the aging

ticket seller to come over and lead you to the street and turn you over to

the beat cop who would run you home if you pissed him off.

It was the perfect place to see “Attack of the Crab Monsters,”

“The 7th Voyage of Sinbad,” “Robot Monster,” or “World

Without End.” It was also where I saw “Blue Denim,” a lost

teen classic starring Carol Lynley and Brandon de Wilde on my first ever date

with the dark and mysterious Juanita who had an older brother who wore rumble

rings and ran with a gang.

But my usual movie Saturday consisted of finding fifty cents to pay

the entry fee to the dark aisles of the Hobart and that meant collecting empty

soda bottles and getting the two cents or a nickel that each bottle would

bring. Sodas were still mixed at formica and chrome counters to the sound

of jukeboxes in those days but empty bottles were plentiful around apartment

buildings and homes.

There was another method to collect the money and it required fishing

line, a padlock and some glue. On one corner of my block was a subway station

and near the station was a bus stop. The people who lined up for the bus would

stand over the grate that provided ventilation for the subway. As they fumbled

for change for the bus, some of it would drop and fall through the grate to

the flat area below. With a little glue on the flat edge of the padlock, we

would slip it through an opening in the grate and slowly lower it to the coins

below using the fishing line. It was tedious and required patience and depth

perception but it beat the hell out of collecting bottles. Unfortunately,

it wasn’t as predictable or as reliable as collecting bottles. Laziness

always wins over clumsiness.

And now, comfy in bed, my laptop nearby and DVDs piled up as so many

madeleines, I can pursue the important films of my past and notice those little

things in flicks that memory has lost. Seeing “Lady From Shanghai”

again was an unnerving event. It was like finding a lost photograph of a long

ago lover and realizing just how much you had idealized her in memory and,

now, looking at the picture, you can’t even recall what originally drew

you to her.

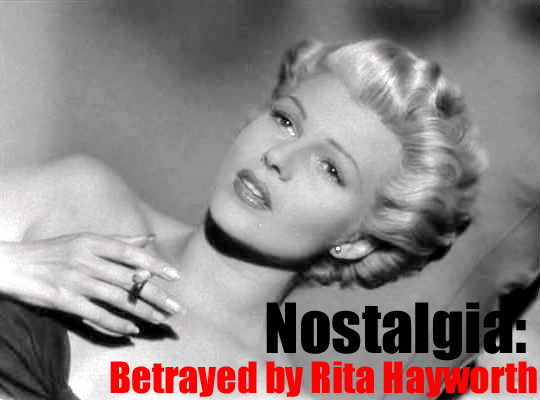

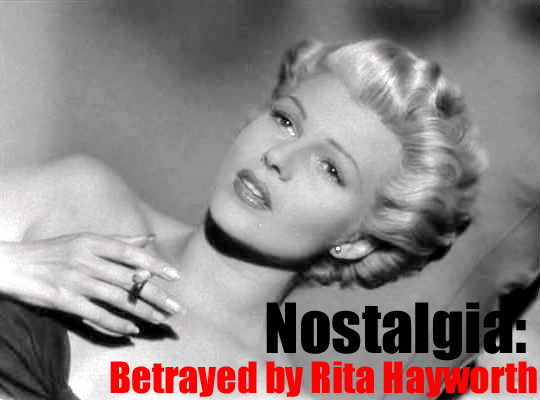

“Lady From Shanghai” was the only movie that I really

liked Rita Hayworth in. At one time, Hayworth was a mythic character whose

image would show up in the oddest places. Besides Manuel Puig’s novel, Betrayed by Rita Hayworth, it was pasting posters of Hayworth around

his town that was the job of Antonio Ricci in Vittorio De Sica’s “The

Bicycle Thief.” Yet, I never got Rita Hayworth until Orson Welles cut

her hair and dyed it blond. She – among the breaking mirrors –

was about all I really remembered about “Lady From Shanghai.”

And now, after having seen the film again, she is still the

only thing that I remember from that movie. How Orson Welles maintains his

credible reputation these days astounds me. With the exception of “Citizen

Kane,” his films are so severely disappointing that I wished I had never

remembered Rita Hayworth at all.

While I could digress into an exploration of Orson Welles and how “Lady

From Shanghai” was such a disappointment (to say nothing of “Touch

of Evil”), it’s the actual viewing of films and how films are

becoming almost disposable these days that interests me at the moment. Back

in my Hobart viewing days, if you missed a film that was it. Maybe some day

it would show up on Million Dollar Movie or The Late Show although that would

be pure serendipity.

The last time I went to an actual movie theatre was during the 2006

Tribeca Film Festival and I went because I had a free pass and the theatre

was just a block away. Going to the movies in New York City has become such

a drag and the films so lame that I’d rather catch up on older films

that I missed or loved rather than stand in line with blabbering cell phoners

and being annoyed by all the chatter during the show. It makes me miss the

old Hobart matrons who could quiet a whole multi-plex with two whacks of a

flashlight.

It’s more than that, though. There is something almost intimate

about watching DVDs on my laptop with headphones and better popcorn. The only

film that I can think of that absolutely needs a theatre experience is a midnight

showing of “The Rocky Horror Picture Show.” That was an exceptional

phenomenon and I’m glad I caught it before it disappeared.

Once it was illegal to own films. When I was in my late teens I had

two friends who were film fanatics and they had a friend who not only had

his own 16 mm projector, he also owned films. We spent the afternoon watching

a couple of episodes of “Sgt Bilko” and then the feature was “A

Man For All Seasons.” The showing was all very clandestine and conducted

along the lines of a heist movie with secret meetings and people vouching

for one another in a one storey stucco house in Queens. Roddy McDowell, as

I remember, had been arrested during those days for owning a copy of “National

Velvet” and it made the news so the studios could make a point about

black market films.

These days, the latest flicks are sold from folding tables on the

street in Chinatown or Union Square or Broadway. With options like NetFlix,

you can get almost any film in the mail. My source is the New York Public

Library. From my laptop I can browse the catalog and reserve films to be picked

up around the corner after they notify me by email. The local branch in my

neighborhood is small and yet I discovered Jean-Pierre Melville there and

found the rest of his work in the catalog. I also stumble across other flicks

I missed like “Central Station” or “The Motorcycle Diaries”

or classics such as “Tokyo Story” or “Ikiru.”

There is something different about a film when it stops being a shared

event. To me, it becomes much more personal and at first I thought that was

why I was being attracted to those films that seemed to be more personal,

those made by directors considered to be artists. That was just another illusion.

This became clear to me as I watched Ingmar Bergman’s “Persona,”

a film I hadn’t seen since its first run. On a one-to-one, personal

viewing, the film seems more a study of cinematography than a narrative on

feminine role-playing or role-playing of any kind. It’s such a beautiful

– but ultimately empty – film that ends with camera tricks rather

than reaching the destination of where the characters seem to be going through

their acting or Bergman’s ideas.

Maybe that would have been apparent in some downtown art house showing,

yet what I’m finding these days is that I’ve become more concerned

with the actual narrative of films and direct personal viewing makes that

narrative more accessible. Movie viewing has now become more about story than

about anything else and finding a story that is compelling rather than manipulative

is what seems to be driving my interest in films these days.

It seems to come down to expectation – as everything does –

and I find my expectations have gained a fluidity that I didn’t expect.

But isn’t that why we delve into things in the first place?